How sustainable is your style?

Can you look at a building and tell if it’s green? Sometimes, appearances can be deceptive. We clue you in on what really makes a building environment-friendly

Sustainability is the buzzword. Every manner of building makes a claim to “greenness” today. While there are various ways of judging how green a building is, we often assume its look also offers a clue.

This seems reasonable. If a building is made largely of a material that consumes less energy and produces fewer emissions, the building is likely to be greener than others. Buildings that expose stone, brick or a wood skeleton consume less cement because they are not plastered. Also, if this material is local, little energy is consumed in transportation. So can there actually be a green look for a building?

This seems reasonable. If a building is made largely of a material that consumes less energy and produces fewer emissions, the building is likely to be greener than others. Buildings that expose stone, brick or a wood skeleton consume less cement because they are not plastered. Also, if this material is local, little energy is consumed in transportation. So can there actually be a green look for a building?

That depends on how the question is phrased. We may ask, “Can we judge how sustainable a building is from its looks?” Or “Are there some aesthetic values that lead to more sustainable architecture?”

Let’s take the first question first. From the late eco-architect Laurie Baker’s buildings in Kerala, we may conclude that using natural materials and showing them off will lead to a greener building. Such strategies reduce the use of energy-guzzling materials such as cement, steel, aluminium and glass. Yet as Surya Kakani, an Ahmedabad-based architect who has built several eco-sensitive institutional and industrial facilities, says, “A building in mud may not be truly green in its impact if the mud is transported from a faraway location, using up a lot of fuel.”

Waste material locally available may be the best. Some years ago, Kakani used earthquake rubble to build load-bearing walls for a school in Rajkot, which he then plastered and painted—a conventional look with deep green veins. At a recently completed garment factory in Ahmedabad (which is day-lit and naturally ventilated), he exposed the mix of fly-ash bricks (75%) and burnt bricks (25%) in a distinctive look that flaunts environment-friendly underpinnings.

Size matters too. An air-conditioned, 5,000 sq. ft bachelor’s pad, even if built with local mud, would not be the best illustration of sustainable architecture. In this case, size alone would negate the low-energy consumption of the building material, even before power-guzzling appliances come into play. The natural look of mud construction can hide a very unnatural attitude to consumption.

Perhaps there is no green look then. Or maybe looks have nothing to do with sustainability.

A less sustainable look?

Consider the other side of the coin—is there an aesthetic that is inherently non-green?

One look at oversized glass and aluminium composite panel (ACP) building blocks in Gurgaon, neighbouring Delhi, or Whitefields, near Bangalore, and you know these are not sustainable buildings. The huge glass walls face any direction, including the west, from where the hottest low-angle sun streams in. Glass lets in light and traps heat. So these corporations must consume a lot of energy (and cash) to keep the interiors cool. And all this because of the “progressive” look they desired.

Certainly, the glass and ACP facades are an aesthetic choice. We have been conditioned by the use of glass in American skyscrapers into believing that it best expresses corporate identity. Over the second half of the 20th century, private corporations rose in power, and glass became the architectural motif of power and prestige.

So much so that glass (and ACP) is the exterior material of choice for many non-corporate entities, even many governments. You can find cultural centres and small businesses adorned with glass even in scorching semi-desert climates. The state-built PL Deshpande Maharashtra Kala Academy, built over the old Ravindra Natya Mandir at Prabhadevi in Mumbai, is an example. A small hotel in Bhuj, Gujarat, in which I stayed two weeks ago, had a large glass surface catching the hot morning sun. Behind the glass was the air-conditioned lobby.

So the glazed look would certainly seem to have an unsustainable ecological impact. However, things are not quite so simple.

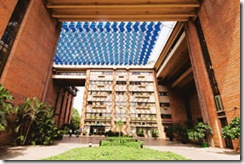

Indiscriminate glazing can certainly make buildings unbearably hot and increase energy consumption in the form of air conditioners. But glass is not the villain. If expanses of glass face shaded courtyards and let in reflected light, we could get free daylight, while avoiding the heat and glare. The Apollo Tyres headquarters, designed by Morphogenesis in Gurgaon, does this with the style of a typical corporate office in glass, aluminium and stainless steel.

Climatic considerations

The real problem is our fascination for a particular look irrespective of its climatic and ecological appropriateness. Through the buildings they design, architects often engineer and strengthen this fascination. If large numbers of architects continue to favour one look, they push people’s imagination towards it.

Yet, sometimes, the work of even a single architect can counter this—such as that of the late Joseph Allen Stein, who nudged the imagination of architects and laypeople in New Delhi towards a more nature-friendly taste. The values embodied in Stein’s work, such as the brick-walled India Habitat Centre, constitute a much more ecologically responsible approach.

This puts a special responsibility on architects. Not only do they need to know the actual ecological impact of their design decisions, they must also consider the cultural impact. “Whatever aesthetic an architect wants to explore must be explored responsibly,” says Jaigopal G. Rao, an Ernakulam-based architect with expertise in eco-sensitive architecture. “We can’t casually choose a look that needs energy-guzzling materials and goes against climatic logic.”

For his part, Rao has already developed a unique style of building, combining bamboo with concrete to create light, airy and ecologically gentle architecture.

Now, it’s up to the rest of us.

*******

Pointers for greener buildings

• Reduce: Build as little as possible, so that you consume little even with conventional technology. If possible, reduce the use of energy-guzzling materials such as cement, steel and aluminium. Look for alternatives. A tip: Labour-intensive technology can often reduce total fossil fuel energy use

• Reuse: Buy doors, windows and similar building parts from second-hand dealers

• Recycle: Recycle water, waste, garbage and anything else you can think of

• Reset: Expectations of comfort and style can be limited to what may be naturally available through good architectural design without mechanical equipment. If you must use an air conditioner, accept a temperature of 27 degrees Celsius, instead of 22, and save energy costs. Also, change your lifestyle to save every drop of water and electricity

• Resource: Local material saves transportation energy. Cement, steel and the tiles available in your local store don’t count as local material. Instead, explore the possibilities of local stone, mud, bamboo and terracotta. Also, explore ferrocement and innovative brickwork techniques