From SF Chronicle, written by Joe Garofoli, Chronicle Staff Writer

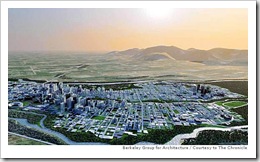

Sabeer Bhatia plans a 17.6-square-mile city of world-clas… Nano City, as shown in this architectural rendering

A few days after his 29th birthday, Sabeer Bhatia sold Hotmail, the company he co-founded, to Microsoft for $400 million. Selling the Web-based e-mail service bought him a swank Pacific Heights condo with a panoramic view, buzz as the next hot Silicon Valley player, boldfaced name recognition in the Indian press – and eventually, one incredibly unchallenging year off playing golf and jet-set partying.

He became haunted by the question common to those who find wild success at a preternaturally young age: Now what?

Granted, over the past decade, Bhatia has had his hand in several technology startups and post-startups both here and in India, some mildly successful, some not. But his latest project is one that comes from the heart: He is trying to develop an Indian version of Silicon Valley, a sustainable city spread over 11,000 acres in northern India that he envisions will be home to 1 million residents employed largely by world-class universities and A-list companies that act as the country’s idea generators. He calls it Nano City.

One problem: Until recently, Bhatia knew nothing about developing cities. The 39-year-old San Francisco resident is an electrical engineer by training and profession. And with a ton of cash in the bank, the last challenge he thought he would face is the hassle of navigating India’s cash-under-the-table democracy, while preaching sustainable development. India, with a population of 1.12 billion, is beset with energy and infrastructure problems; most citizens don’t have access to safe drinking water.

Major developer

But now – after spending $4 million of his own money and learning some hard lessons about international development – Bhatia’s project could be on the brink of starting. This summer, he partnered with a major Indian developer that pledged funds to help purchase the land needed in the northern Indian state of Haryana to break ground on Nano City.

But major hurdles remain, and the project could easily fail.

Bhatia wasn’t thinking about urban development when the idea for Nano City first surfaced in March 2006. He was watching a cricket match in India with a government official from Punjab, pitching a plan to bring premier U.S. educational departments in science and technology to Indian universities.

"The education over there, until the undergrad level, is pretty good," said Bhatia, who attended Indian schools before receiving an undergraduate scholarship to the California Institute of Technology and earning a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University. "But when it comes to grad school, it just falls off the cliff in terms of quality."

The official asked what he needed to get the project done. Bhatia casually told the official that he could lure A-list U.S. universities to the area if the government provided land and financial incentives.

A few days later, Bhatia returned to the United States, having agreed to write a proposal. But he considered the conversation the kind of casual banter one has at a sporting event, something not to be taken too seriously – until Naval Bhatia, Sabeer’s cousin and an attorney, mentioned the conversation to a friend, an official in nearby Haryana.

The Haryana official told Naval Bhatia, "Why should Punjab get him? We want to offer him even more."

"It’s a common occurrence, especially in developing countries," said Seshan Rammohan, executive director of the Silicon Valley chapter of the Indus Entrepreneurs, an international organization of Indian and other South Asian entrepreneurs. "When someone gets some notoriety, as Sabeer did after selling Hotmail, they get bombarded with offers.

"If someone like Sabeer is attached to a project, then the thinking is: Other people will want to invest," Rammohan said.

Within days, Bhatia returned to India to speak with the Haryana officials. They discussed an 11,000-acre spot about 15 miles east of Chandigarh, Bhatia’s birthplace and one of the few planned cities in India.

Not another Bangalore

The idea of an Indian Silicon Valley began to resonate with Bhatia. He didn’t want to create another Bangalore, the traffic-tangled, booming thicket of a city where he had grown up, best known for its outsourcing operations for American companies. He wanted a place where Indian-germinated ideas could flourish and where young Indian students could receive a first-rate education.

In pursuing the Nano City project, Bhatia found the answer to the question, "Now what?" If it succeeded, he could make millions of dollars more. "But my reason for doing this is to leave behind a legacy," Bhatia said.

"How many times in our lives do we get a chance to build a city?" he said. "How many times do we get an opportunity to fix some of the problems that affect 1.1 billion people – that’s one-sixth of humanity."

Bhatia is aware that planned cities often fail. To avoid pitfalls, he intends to involve "the right partners, do proper design, provide basic things that you and I take for granted here."

Atypical entrepreneur

Before calling in the bulldozers and cranes, Bhatia boned up on development. He ordered dozens of books on Amazon.com and picked the brains of Stanford professors, real estate developers, even the guy who renovated his apartment.

"Why not?" Bhatia said. "He was a guy in the construction business."

That summer, his assistant set up a meeting with several UC Berkeley professors. The professors had met Bhatia’s type before.

"A lot of these rich entrepreneurs come to us, thinking they have all the answers," said Nezar AlSayyad, a professor of architecture, city planning and urban design at UC Berkeley who has been involved in projects around the world. "I expected him to be like that."

AlSayyad grilled Bhatia during their first meeting, asking for specifics and trying to ferret out his motivations. The professor silently shuddered when Bhatia mentioned he liked Santana Row, the San Jose development that is one of the few spots in Silicon Valley that tries to create a public square with a mix of retail and housing. AlSayyad thinks it is part of suburban sprawl.

Nonetheless, AlSayyad came away impressed with Bhatia, and for one simple reason. "He listened. And he asked questions."

Social, financial impact

In early 2007, Bhatia flew nearly two dozen students and faculty to the proposed site in India, where for nine days they met with local officials and residents, and studied the topography of the site. Over the summer, the group explored green ideas, such as ensuring that a public park was within a five-minute walk of any point in the city and how best to create efficient mass transit.

"Sabeer really pushed these ideas of sustainability," said Stefan Al, lead designer of the project. "A lot of these ideas have been tried before, but not all together in one place."

In addition to contributing design ideas, the students challenged Bhatia with questions about Nano City’s social and financial impact. They posed one particularly challenging question in the developing world: What will happen to the people who live in the roughly two dozen villages where Nano City would be built?

Many belong to families who have lived on small plots for more than 100 years. In May, 71-year-old Karam Singh, a farmer who owns 25 acres near the proposed project site, told the Indian Express, "Even my great grandfather was born here. How can I sell this land?"

Land prices in the area have quadrupled since the project was announced, and currently stand at about $50,000 an acre. Rafiq Dossani, senior research scholar at the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center at Stanford University, believes land acquisition from villagers will pose the biggest problem.

"The state leaves it to the businessperson to negotiate his way through the thicket of corruption and lack of information that typically surrounds land records in rural areas," Dossani said. "A piece of agricultural land will often have multiple claimants, indebtedness and prior claims over the generations."

Mt. Everest challenges

Last fall, Bhatia began purchasing the land, a few acres at a time. After acquiring about 50 acres, he found that "every subsequent acre of land we were buying was more expensive than the previous one," he said. In November, he stopped the process and hired four attorneys to research who owns every plot.

Meanwhile, he was having trouble raising money. Nobody wanted to invest. The name "Sabeer Bhatia" opened some doors, but he was repeatedly told he lacked sufficient real estate development experience.

Last month, Parsvnath Developers Ltd., an Indian development firm with experience in land acquisition, agreed to pick up a 38 percent equity stake in the project. The move, Bhatia said, will enable him to break ground on Nano City early next year and develop its first 1,000 acres.

Bhatia plans to offer free university education to the children of landowners. "We think that over 95 percent of all the farmers actually want to sell," he said. "We think this will put pressure on that remaining 5 percent of people who are maybe greedy for more money."

If they don’t sell, Bhatia said, "We are ready to walk away. … You can’t build a city around a farm."

If he does succeed, then the hard part comes: developing Nano City in an environmentally sustainable way in a rapidly growing country. "This is not Sabeer climbing Mount Everest," said entrepreneur group leader Rammohan. "It’s Sabeer climbing Mount Everest with the city of San Francisco on his back."

India facts

Although India occupies only 2.4 percent of the world’s land area, it supports over 15 percent of the world’s population. India’s median age is 25, one of the youngest among large economies. About 70 percent of the population lives in more than 550,000 villages, and the remainder in more than 200 towns and cities.

Population: 1.12 billion, 27.8 percent living in cities; annual growth rate: 1.3 percent.

Workforce: 450 million; agriculture – 60 percent; service and government – 22 percent; industry and commerce – 18 percent.

Literacy: 61 percent.

Gross Domestic Product (2007): $1 trillion.

Real growth rate (2006-2007): 9.4 percent.

Per-capita GDP (2006-2007): $909.

Trade: Exports (2006-2007): $127 billion, $22 billion of which are software exports.

Major trade partners: United States, China, EU, Russia, Japan.

Source: U.S. Dept. of State, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs (June 2008)

Nano City’s green features

Sabeer Bhatia intends to incorporate green and sustainable building practices into Nano City’s design – a rarity in India, where availability of power and water is inconsistent. Stefan Al, the Berkeley-based lead designer of the first phase of the Nano City, is planning the following features:

— Fifty percent park and open green space, with only local, self-sustainable vegetation planted in landscaped areas. A park will be less than a five-minute walk from any starting point in the city.

— Shaded walkways, arcades and tree-lined boulevards to encourage walking.

— A rapid bus-transport system, where buses will travel in dedicated lanes.

— Living machines, such as surface-water treatment plants that convert wastewater into chemical and odor-free drinking water by using algae, plants, bacteria and micro-organisms.

— Power generated by windmills and photovoltaic technologies.

— Green roofs that capture rainwater.

E-mail Joe Garofoli at jgarofoli@sfchronicle.com.

One reply on “Sabeer Bhatia to build sustainable Nano City in India”

A very well thought , informative ,article.

Are their wnoghf support from various sectiopns , like Govt, industeries, manpower etc available.

These types of ideas must be encorgaged , by Govt. and industeries laso.

Till noe real estate in India means , a thoghtless construction of houses , without having , user in mind. No customer satisfaction, value for money, time commitment are there in this industry.